How the New Mexico Wildfires Reshaped My Meaning of Home

There’s nothing quite like a massive natural disaster threatening your livelihood to help you prioritize your life and reassess your meaning of home.

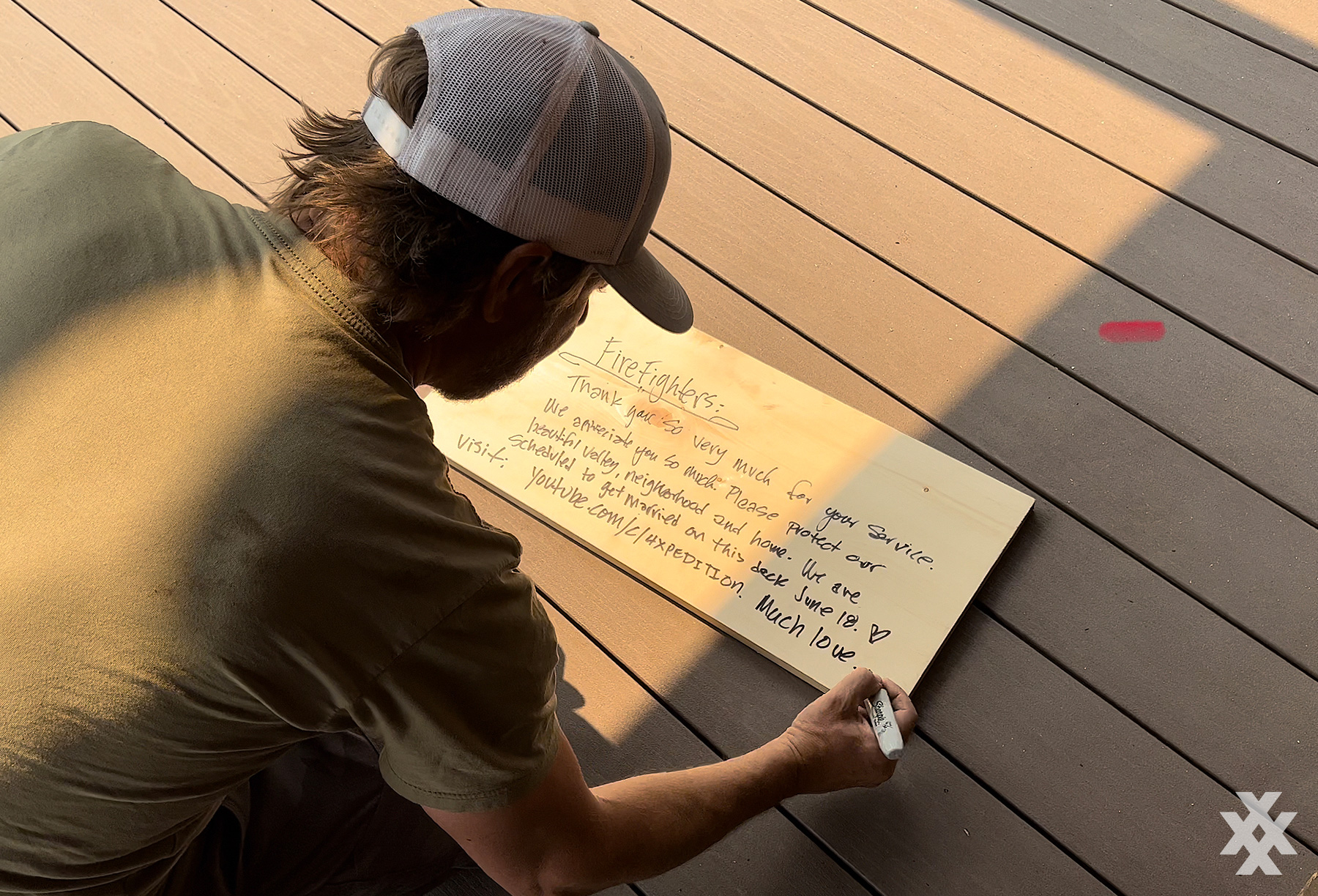

For 14 days, my fiancé, Heather, and I were evacuated from our property in Black Lake, New Mexico. Our evacuation interrupted 10 straight months of rebuilding and remodeling our little cabin to make it a place we could affectionately call home. Over the course of our evacuation, we kept our eyes and ears acutely focused on the twice-daily live updates by the forest fire experts overseeing nearly 3,000 fire suppression personnel. The fire fighters were up against a blaze that grew to more than 300,000 acres.

Last July, we closed escrow on our corner of heaven and began demolition of the structure’s interior. The little cabin we purchased on 4.25 acres had not been occupied for more than 12 years. When we found her, she had been overtaken by insects and rodents. The walls of the log structure leaked from woodpecker holes. The front porch was rotting away. The property had little electrical connectivity other than a ceiling light and no plumbing other than a drain hole in the floor for the kitchen sink to flush gray water through a PVC pipe onto the ground. On detailed assessment, the little cabin had good bones and a solid metal roof. At the time we took possession of the property, the little cabin was far from livable according to our collective standards.

When I try to relate to such deeply rooted culture, I find I have difficulty getting my arms around its magnitude.

We both consider ourselves adventurers at heart. We’ve spent a great deal of time sleeping in our cars on extensive camping trips and otherwise roughing it on the ground in remote backcountry. Though we’ve lived comfortable lives, we’ve also lived quite modestly in one-room structures. I can attest that each of us is well acquainted with a minimalist lifestyle. After spending years adventuring and exploring the outdoors–often in far off corners of the world–we both decided that our next great adventure would be to make this tiny cabin a place where we could feel at peace and live in harmony with nature. So, we set out to create what we envisioned to honor that adventure and spent nearly a year completing it.

Then this spring, under extremely dry and windy conditions, the United States Forest Service authorized controlled burns in the region that quickly grew out of control. As the Hermit’s Peak Fire and Calf Canyon Fire grew, they merged into one massive inferno that rapidly became the largest fire in New Mexico history.

Though the blaze [as of writing this article] had taken no lives, the fire was only 50% contained, had scorched more than 316,000 acres, and destroyed more than 300 structures. As the fire advanced, it made its way northeast and we found ourselves right in its path. As the days passed, smoke filled the air and ash blanketed everything on our property. Then, the fateful day came when we were told to evacuate. After packing our things and departing, we watched in anguish from afar as reports came in that homes and countless acres of stunning landscape were being engulfed by flames. Fortunately for us, the fire never reached our valley. Forest fire personnel were successful in extinguishing the portion of the fire that had been advancing toward us. Others were not so lucky.

Contemplating the massive devastation, one can only appreciate the loss when getting to know the people, culture, and history of the State of New Mexico. For me, my contemplation initiated this article. My ponderings led me to contemplate what “home” really means. Though I believe the true meaning is embedded in the beliefs of each beholder, I can’t help but consider that to get through such devastation, one must acknowledge and embrace that home is a state-of-mind and not a physical place. How else can anyone come to terms with such loss other than to detach from it? As I have since come to realize, native New Mexicans simply cannot and will not detach. Here’s why.

New Mexico is a distinctly unique region of North America. The turbulent history here has shaped this great state into its own melting pot of cultural diversity and rich tradition dating back a thousand years. To most of those who have lost everything in the wake of this fire, a house burned to the foundation has exposed much more than brick and mortar. It stripped away layers of legacy established by beloved ancestors who handed sacred land down through many generations. Culturally, I assume, the burning of a casita or ranchito can be compared to the scorching of Jesus Christ on the cross. Maybe that’s an over exaggeration, but, these are significant, sacred, and deeply cherished lands and structures.

As the fire advanced, fire strategy experts vowed to protect “values” or private property structures and historic sights. Yet, the forested peaks, slopes, and valleys in-between are no less significant to the people here. The stunning landscapes throughout the historic land grants have been the hunting and fishing grounds of those who reside here season after season for centuries.

When I try to relate to such a deeply rooted culture, I find I have difficulty getting my arms around its magnitude. I recall my uncle on my father’s side once instructing me to not spend more than ten years living in one single place. His message rang true for me at the time. To me it meant that life can become dull and repetitive when you stay in one place for too long. I embraced the idea that living in new places is a means to keep life fresh and interesting. The significance of living on land that my distant ancestors cultivated and built a life dependent on is largely foreign to me. Yet, I can sense the emptiness the people of this region must feel from such a significant wrath scorching the faces of beloved family members long departed. Here is where I begin to understand what home means to the people here.

FROM OUR SPONSOR

Many of the families that experienced loss from this devastating fire own their land outright primarily because the land was given to them by generations before them. Because so, I presume, many aren’t required to hold homeowner’s insurance like is required of a homeowner with a lien holder. This adds fuel to the fire as struggling families have no recourse to rebuild. Property owners are completely dependent on funds from FEMA and their own blood, sweat and tears. Any other help comes from gracious neighbors lending a hand who are part of the woven fabric of the region–extended family.

Our property also has no mortgage. We’ve also invested our heart and soul creating and establishing what we have. We’ve worked hard. We’ve often been pushed to our limits. What’s different, however, is the sense of legacy. Legacy is what I intend to create on my property but it starts with me. There is no history here for us beyond the past year of effort and the subsequent connection we’ve established with our property, the region, and each other in the process. Along the way, we named our cabin Songbird and our property Mantle Rock. In June, we intend to get married here on the front steps before 100 of our friends and family members. As we take each step forward here, history is made and legacy established. With each step, a deeper connection is made. I can only imagine what 300 years of connection with the land can do to a heart, mind, and soul. The only word I can bring forth is ‘sacred’. The meaning of home to the people of New Mexico is sacred.

My parents lost their home in an Arizona wildfire years ago. That family experience left a significant impression on me. I vowed to take great caution in selecting a region and property to build my legacy upon. I know the devastation such a disaster has on the hearts of those who deeply connect with a home created with their own hands. Yet, when I arrived here, I fell immediately in love. My rational mind was pushed aside. I actually prayed out loud for weeks straight that my land and the surrounding valley be protected with significant rainfall. I was blessed to have my prayers answered last summer as the region received more rain fall than it had seen in the previous 40 summers. This past winter season saw an average snowfall. In spring, the temperatures rose above average and the relentless winds of winter continued on. The winds kept everything unseasonably dry. With very low relative humidity and the strong dry winds, a perfect storm developed before fire season even had a chance to kick off.

Residents were told to avoid using grills, building camp fires, and to avoid any activity that could spark a fire. Yet, the Forest Service apparently believed otherwise with their own practices.

The Hermit’s Peak and Calf Canyon Fires reminded me of the controlled burn practices I witnessed last fall just over the hill outside of my neighborhood. The land just beyond the trees opens up to a vast valley of tall grass. We affectionately refer to it as “The Valley of the Herd” because we regularly view hundreds of elk charging across it. The valley is the property of the New Mexico State Trust and twice a year a team is assigned to perform a controlled burn of it.

When I first experienced the burning last fall it alarmed me. I had never owned property so close to a controlled burn. Throughout the day, the team lit ground fires, piled heaps of deadfall and set them ablaze. Late that afternoon, a representative came to my door. He told me the fire was under control and that all had gone well. I could see the fire burning as I looked over his shoulder. I asked him if there would be anyone overseeing the fire overnight. He responded quite vaguely that they would if they could find someone to do so. But, he wasn’t sure. That evening after dark, I walked over to the edge of our forest in our neighborhood to observe the fire from our side of the barbed fence. The wind was gusting. I counted more than 40 individual fires burning with many piles burning more than 10 feet high. The winds were blowing embers into the air and casting them far across the burn area. The closest burning pile of deadfall was about 15 feet away from the fence. On my side of the fence the forest floor was covered in knee-high yellowed grass and thick, moisture parched pine. There wasn’t a soul around. Not one single fire fighter in sight. The fires were burning and blowing in the wind completely unmonitored.

That night was a very long night for me. I remained awake well into the early morning watching out the window for spot fires into our forest. Fortunately, none sparked. That experience shaped for me the reality that controlled burn protocol needs to be addressed. With the Hermits Peak and Calf Canyon fires still ablaze and the US Forest Service admitting they were the cause, my belief is now solidified. And, for better or worse, forest management protocol has to change. And, just as I can be held accountable for causing a wildfire, so too shall the Federal Government–including the individual personnel who authorize controlled burns that result in out-of-control wildfires.

No matter who is responsible for the blaze–human or mother nature–those who’ve experienced the loss must contend with what is. Life will go on and those who sat as spectators to the devastation will fade into the dismay of a blackened forest. The families will be left to pick up the pieces, counting on one another as they always have to rebuild their sacred casitas and ranchos. They will flourish again with the strength and fortitude they’ve inherited from generations past. Their calloused hands that have worked the land to sustain their families will be used to rebuild upon a foundation of legacy. As time passes, another generation will receive what is rightfully theirs. The flora and fauna will spring to life once again for another chapter of an incredible story of spiritual strength.

This is true New Mexico. She has much to teach a newcomer like me. To get to know her is to get to know and befriend those who’ve found a way to exist here for centuries. Living in harmony with the land and being embraced by the people here can only be achieved by understanding the history and culture that shaped the region. The trees that have stood in these forests have played witness to that history. They’ve held significant wisdom. Millions have burned to brittle from this wildfire and with them their stories lost. With their loss, we arrive at a chapter’s end. We can only hope their wisdom lives on in the families that have walked among them over generations. As new saplings take root, so shall the next generation of New Mexicans of this region. Together they shall weave a new chapter of New Mexico history adding another layer of legacy.

So, is ‘home’ a state-of-mind? I’ve come to believe it is. The people of this state have embraced home as a culmination of mind, body, and spirit. Home is a way of life. It is a perspective. It is a sacred space, a tightly woven community, togetherness of family, neighbors you can count on, and a trust in the land to provide. It is an internal strength to always move forward no matter the circumstance. The structures and land they inherit is the canvas for which a legacy has been painted. As the years pass and events unfold, another stroke is applied. We can all learn a lot from the people here. If we can learn to embrace their meaning of home, we will find our belonging in a global community with a collective state-of-mind. Home will surround us and flow through us. And, together as a united front, our legacy will live on.

Article written by: Scott Leuthold

Photographs by: Scott Leuthold

Thank you for your consideration and time to read this article. All photographs were captured from this region of Northern New Mexico over the last year. These images have been shared throughout this article in an effort to illustrate the stunning beauty that, in many cases, has now been lost to the Hermits Peak Fire and Calf Canyon Fire.

To obtain permission to repost this article or use any photograph displayed herein, please inquire here.